First time on board

I boarded the R/V Roger Revelle around 8:00 PM on Friday the Sixteenth and quickly got lost looking for my room aboard the 273-foot research vessel. I spent nearly twenty minutes wandering the upper decks looking for an entrance into the ship, only to be guided inside after another science crew member arrived and showed me the way. Most of the scientists and volunteers aboard sleep in the staterooms on the First Platform, the floor below the main deck, or in staterooms on the First Deck. The staterooms are comfortable and built for two people with a bunk bed in each room, a desk, storage cabinets for personal belongings, a sink and mirror, and a shared bathroom, equipped with a toilet, shower (with surprisingly good water pressure), and heating lamp between two adjoining staterooms. All the cabinets and drawers on the ship come with a lock or a latch to ensure nothing opens and then slams closed due to the rocking sea.

First Day

My first day aboard the R/V Revelle was hectic and disorienting. I woke in complete darkness and found I was late for a safety meeting. I had to remember my assigned number to make sure everyone was accounted for. I’m number fifty-four. Breakfast was right after and I had no idea where the galley was, so I just followed the herd of people going towards the galley to find my way there. They served omelets, hashbrowns, pancakes, bacon and sausage, and fresh fruit and yogurt. And lots of coffee. Afterward, the Zooplankton lab team, led by Dr. Moira Decima, then did a practice Bongo tow off the starboard side of the ship. The samples collected from the port side of the net are brought into the wet lab for processing. The port side sample is split into three portions. One portion is transferred to the “gut cup,” which is then vacuum filtered and preserved in a dewar containing liquid nitrogen for later analysis. The other two portions are then size fractionated over a series of five sieves with decreasing mesh sizes and vacuum filtered for biomass and gut fluorescent analyses. The biomass samples are then preserved in a -80℃ freezer and the gut fluorescent samples are stored in a dewar containing liquid nitrogen. Each sieve has a corresponding vacuum pump to collect the sample onto a fine mesh filter. The entirety of the starboard sample is preserved in a jar containing a sodium tetraborate buffered 5% formalin solution.

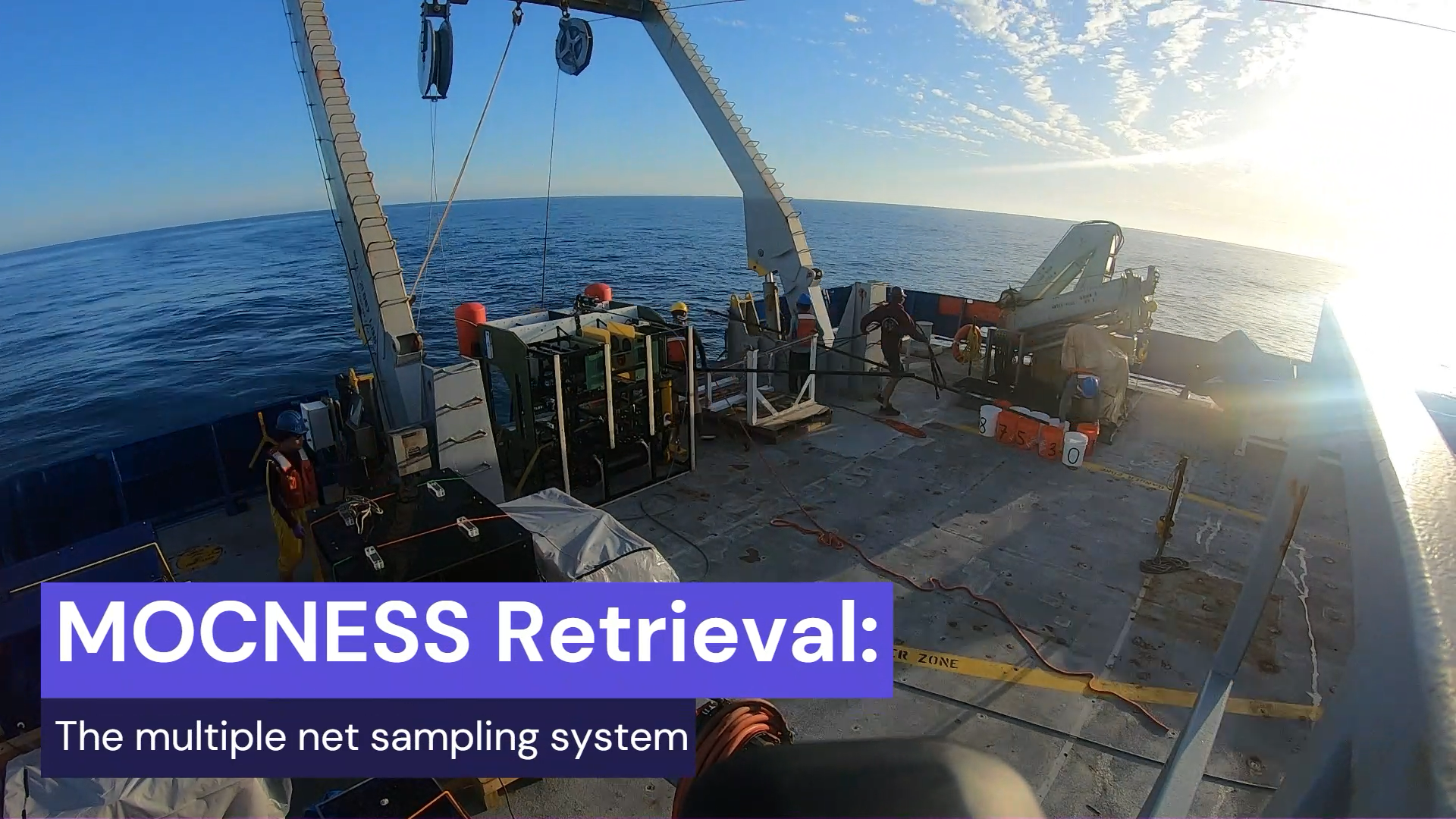

We then all met after lunch in the ship’s library to go over the labeling protocol. Afterward, we did a practice deployment of the MOCNESS: the Multiple Open Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System. Before the net goes into the water, we first have to prepare the net, what we call “cocking the moc,” which involves cocking each of the ten nets of the MOCNESS, a piece of equipment containing ten nets that can be closed while in the water column), by bringing each bar to the top of the rig and latching each metal-wire-trigger into the motor mechanism, making sure that none of the wires are crossed and everything is in its proper order. We then attach the cod ends, where the sample collects, to the bottom of the nets and secure the latches with electrical tape. We bring the net in, take off the cod ends, store them in cooled water, and get to processing the samples, taking anywhere from three to five hours. Half of each net is preserved in formalin, a quarter is preserved in ethanol, and a quarter is size fractioned and kept in Petri dishes for biomass.

We ended the day by having dinner in the galley, served from five to 6:00 PM every day, and going about to different parts of the ship. I ended up reading some of All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy before heading back to my stateroom to get some sleep—a good contrast to life on the water.